‘More precisely, the fidelity of faith matters more than the representation, whose movement this fidelity commands and thus precedes.’ (p30)

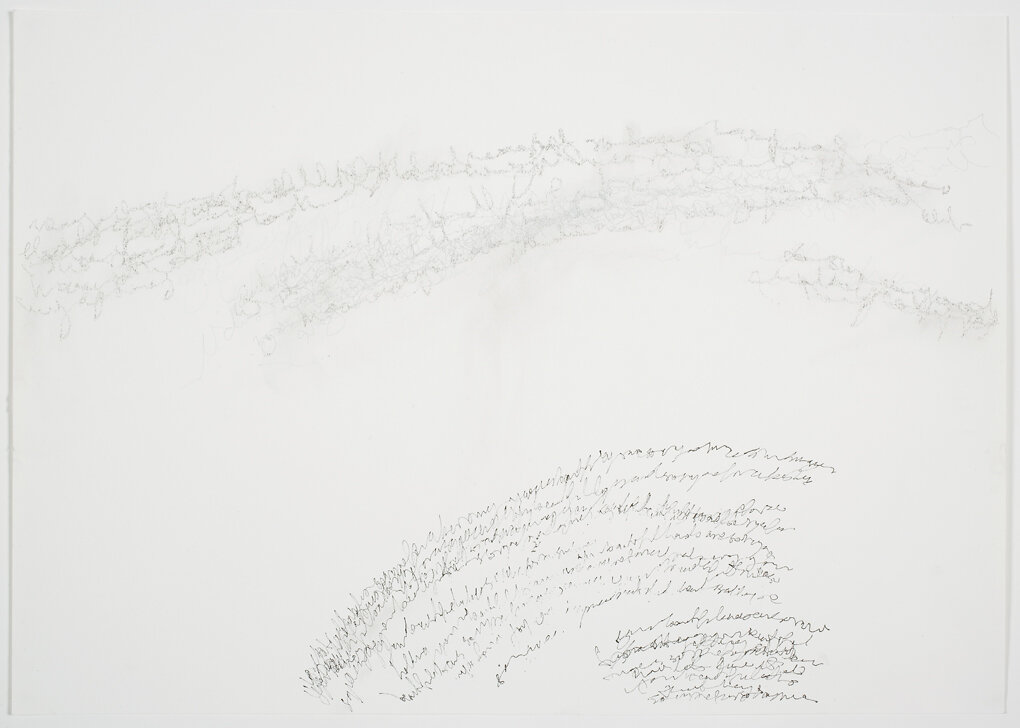

In the series called 'Love Letter', I used a child's toy, the ‘junior sketch-a-graph' (where a pencil is placed in one position on the articulated plastic 'arm' of the sketch-a-graph and a stylus which is used to direct the pencil on another and is intended for tracing and duplicating images) to write a letter to my lover. The ‘junior sketch-a-graph’ is an unsophisticated version of a once useful drafting tool, a mechanical drawing machine used to reproduce maps before photocopiers and computers. The junior sketch-a-graph, it turns out, is unable to replicate with any accuracy and instead turns the writing into a series of illegible scrawls, which wander around the paper leaving only their snail trails as a clue to what was written. This obfuscation maintains the intimate nature of the text, it is only legible to the lover through the medium of shared history.

As in any relationship, the details are only clear to those who are within it. This blurriness then allows a reckless abandonment of discretion, a giddy release, which invites a glimpse into the sacred but leaves the viewer (voyeur) ultimately frustrated. There is a communication failure, through the mediation of the sketch-a-graph the information has been discarded, but in its place is left a natural rhythm, the arcs and swoops of the sketch-a-graph itself, which describe both its possibilities and its limitations and redeem the drawings as things in and of themselves.

Derrida, J. (1993), Memoirs of the Blind, Chicago, University of Chicago Press.